Executive Summary

Our investigation uncovered a coordinated campaign in which multiple Chrome extensions—initially benign and serving unrelated purposes—were transformed into remotely controlled content-injection tools. Although the extensions appeared harmless and requested no special permissions, each was modified to periodically download a configuration file from an attacker-controlled domain. These dynamic rules allowed the extensions to overwrite webpage content, inject external HTML, and manipulate sites visited by the user without requiring a Web Store update.

Infrastructure analysis revealed that the extensions’ malicious functionality was introduced immediately after ownership transfers in the Chrome Web Store, a pattern observed across several cases. In parallel, the command-and-control (C2) domains used to deliver remote instructions were registered shortly before the compromised updates were published, suggesting premeditated preparation of attacker infrastructure. The convergence of identical injection logic, shared architectural patterns, synchronized domain registrations, and post-acquisition code changes indicates that these extensions were compromised and operationalized as part of a coordinated, infrastructure-backed campaign rather than isolated incidents.

Technical Analysis

While each extension presented a different benign feature, the internal code implemented the same high-risk behaviors. Across all analyzed extensions, a recurring hidden mechanism enabled the remote, dynamic manipulation of webpages. In the following we will focus on Malicious Behavior persistent in all spotted extension:

- Remote Configuration Fetching

Each extension contacted an external server every 5 minutes to download a fresh configuration file (config.php or theme.php).

This file contained instructions controlling:

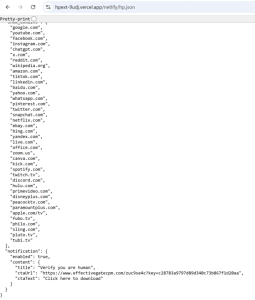

- Which websites to target

- Which DOM elements to modify

- What remote payload to inject

Figure 1. A Regex Matching ‘location.href’

Because these configs come from attacker-controlled domains, the behavior of the extension can be changed instantly, without any update through the Chrome Web Store.

This design effectively creates a command-and-control channel inside the browser.

- Dynamic DOM Injection

The downloaded configuration defined rules such as:

- pattern – regex to match targeted websites

- selector – elements in the DOM to overwrite

- url – remote endpoint that provides injected HTML/text

- attr – the DOM property to replace (e.g., innerHTML, src, href)

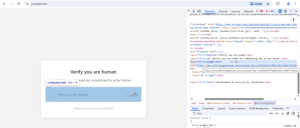

Figure 2. DOM Object Replacement

The extensions used these rules to fetch attacker-controlled content and inject it directly into webpages:

This allows remote servers to:

- Replace login forms

- Insert phishing overlays

- Modify financial or shopping pages

- Inject ads or tracking beacons

- Alter social media content

All without alerts, permissions, or user visibility.

- Persistent Manipulation via MutationObservers

To ensure modifications cannot be undone by the website, the extension uses MutationObserver.

This continuously reapplies injected content whenever the page updates, ensuring persistent and stealthy manipulation.

The extensions share a common architecture designed to allow remote servers to rewrite any webpage the user visits, silently and repeatedly. This constitutes a highly flexible and dangerous browser manipulation framework, masquerading as harmless utilities.

Infrastructure Analysis

Our investigation revealed a coordinated ecosystem of extension ownership transfers, rapidly provisioned command-and-control (C2) domains, and synchronized malicious updates, strong indicators that these extensions were compromised and operationalized as part of a structured campaign rather than isolated events.

- Extension Ownership Transfers and Post-Acquisition Weaponization

Historical metadata from the Chrome Web Store shows a consistent pattern: the extensions behaved benignly until shortly after their ownership changed. Across multiple samples we observed:

- A modification to the listed extension owner or developer shortly before the malicious update.

- No evidence of remote-configuration logic in earlier versions.

- A sudden insertion of:

- Periodic retrieval of remote configuration files

- Rulesets for DOM rewriting

- Beacon calls to install.php

- Support code enabling persistent content manipulation

User reviews corroborate this timeline, noting unexpected behavior immediately following these updates.

This aligns with a known strategy in extension-abuse campaigns: threat actors purchase high-install extensions and retrofit them with a modular malicious framework.

- Temporal Coupling Between C2 Domain Registration and Malicious Updates

Analysis of WHOIS records for the infrastructure used by the extensions reveals a striking temporal correlation.

Key observations:

- Domains were registered days to weeks before the malicious extension versions were published.

- The malicious updates began querying these domains almost immediately after they went online.

- The domains share similar naming conventions and infrastructure characteristics, suggesting centralized provisioning.

This pattern is consistent with adversaries preparing operational infrastructure immediately prior to activating compromised extensions.

- Clean vs. Malicious Versions

Code comparisons between earlier and later versions highlight a clear inflection point:

Pre-Compromise (Benign) Versions

- Contained only the functionality advertised (e.g., image editing, video detection, DOI extraction).

- No external configuration resources.

- No dynamic content injection.

- No persistent monitoring mechanisms (e.g., MutationObservers).

- No debugger or fingerprinting APIs.

Post-Compromise (Malicious) Versions

- Added a remote-configuration retrieval loop (typically 5-minute polling).

- Introduced instruction-driven DOM manipulation using regex-matched rules.

- Embedded a reusable injection engine capable of overwriting arbitrary page content.

- Integrated installation beacons for telemetry back to attacker-controlled domains.

Figure 3. kbaofbaehfbehifbkhplkifihabcicoi before and after

The differential strongly supports the hypothesis of deliberate weaponization after acquisition.

- Indicators of a Shared Toolkit or Unified Threat Actor

A cross-extension comparison uncovered a high degree of structural similarity:

- Identical polling intervals (300 seconds).

- Near-identical logic for parsing remote configuration rules.

- Consistent naming of fields such as pathMatch, selector, applyMethod, resourceLink.

- Recurring remote endpoints (config.php, theme.php, install.php).

- Similar error-suppression patterns and silently failing fetch() calls.

- Matching patterns in how injected content replaces DOM attributes.

| Extension ID | Owner Change | Domain Registration | Malicious Version Pushed |

| kbaofbaehfbehifbkhplkifihabcicoi | 2025-07-19 | 2025-07-27 | 2025-07-30 |

| ijhbioflmfpgfmgapjnojopobfncdeif | 2025-07-23 | 2025-08-20 | 2025-08-27 |

| nimnhhcainjoacphlmhbkodofenjgobh | 2025-07-19 | 2025-08-20 | 2025-08-22 |

| jleonlfcaijhkgejhhjfjinedgficgaj | 2025-04-14 | 2025-08-22 | 2025-08-26 |

| pgfjnclkpdmocilijgalomiaokgjejdm | 2025-07-19 | 2025-08-13 | 2025-08-16 |

| eekibodjacokkihmicbjgdpdfhkjemlf | 2025-09-21 | 2025-09-23 | 2025-09-25 |

| ggjlkinaanncojaippgbndimlhcdlohf | 2024-09-25 | 2024-09-30 | 2024-10-11 |

| ncbknoohfjmcfneopnfkapmkblaenokb | 2024-12-13 | 2025-02-03 | 2025-02-07 |

The convergence across multiple independently branded extensions suggests a single developer of the malicious framework, or a criminal service offering a turnkey extension-weaponization toolkit.

The infrastructure, timelines, and codebase relationships collectively indicate a coordinated operation rather than opportunistic or unrelated abuse.

December 2025 Campaign

LayerX Security continuously monitors cases in which previously benign browser extensions evolve into malicious ones. In December, we identified several additional extensions published by the same authors that transitioned into malicious behavior, revealing a new campaign focused on converting benign extensions into aggressive adware.

The extensions initially appear harmless, implementing a simple functionality. However, alongside this declared functionality, the code also retrieves a remote configuration from an external server. This configuration contains a list of domains on which the extension injects deceptive notifications, each embedding a URL that advances the infection chain.

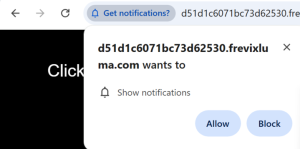

Figure 4. Retrieved Configuration file.

When a user visits one of these domains, a malicious notification is immediately displayed, prompting a “human verification” step.

Figure 5. Fake Notification.

The verification button redirects the victim to successive “not a robot” pages that present only static imagery, while, in the background, a script registers a service worker, fingerprints the user’s device, browser, and operating system, and transmits this information to pushtorm.net. The user is then prompted to grant notification permissions.

Figure 6. Permission Request.

Once granted, the extension repeatedly delivers intrusive advertisements through the same redirection and notification abuse mechanism, effectively subjecting the user to persistent and aggressive adware behavior.

Conclusion

Our analysis reveals that these extensions were not isolated cases of malicious behavior but components of a coordinated and evolving distribution framework. Although each extension presented a different benign feature, they shared a common remote-controlled injection engine, identical configuration logic, and a consistent 5-minute polling cycle.

Infrastructure analysis further shows that most extensions were weaponized only after ownership transfers, and the attacker-controlled command-and-control domains were registered shortly before the malicious updates. This tight coupling strongly indicates a deliberate, organized campaign that acquires legitimate extensions and retrofits them with a modular content-injection toolkit.

Together, these findings demonstrate a clear pattern: a scalable, centrally managed system designed to manipulate webpages, deploy arbitrary payloads, and evolve rapidly without requiring new Web Store updates. This highlights a significant blind spot in current extension review models and underscores the need for stronger detection of remote-config behaviors and post-acquisition extension abuse.

IOCs

Extension IDs – Currently Live Extensions

| ID | Name | Installs |

| kbaofbaehfbehifbkhplkifihabcicoi | PhotoExpress Editor | 5,000 |

| ijhbioflmfpgfmgapjnojopobfncdeif | Extension Canva for Chrome | Design, Art & AI Editor | 1,000 |

| nimnhhcainjoacphlmhbkodofenjgobh | Internet Archive Saver | 2,000 |

| jleonlfcaijhkgejhhjfjinedgficgaj | CapCut Video Editor & Downloader | 6,000 |

| pgfjnclkpdmocilijgalomiaokgjejdm | SnapConnect for Chrome | 2,000 |

| jnkmepoonohhfijlbajdphhinhkoefjn | HP Print Service Plugin

|

1,000 |

| gmmhcbmmnclgmmjimiiefhiagmpamdlb | Edit anything – Boost any page | 780 |

| ooobfpifjkgeopllkalfgkbiefhooggl | Blooket Hacker Pro

|

2,000 |

| cehifnkfcddaeppdajpfldbpommggaca | Kahoot Hacker

|

1,000 |

| eggegjdejilddmnlglakcaigefefcdaf | InteractiveFics

|

350 |

Extension IDs – Removed from Store Extensions

| ID | Name | Installs |

| eekibodjacokkihmicbjgdpdfhkjemlf | InteractiveFics | 3,000 |

| ggjlkinaanncojaippgbndimlhcdlohf | PaperPanda — Get millions of research papers | 100,000 |

| ncbknoohfjmcfneopnfkapmkblaenokb | Vytal – Spoof Timezone, Geolocation, Locale and security | 40,000 |

Domains and Support Emails

- themeassets.site

- pixmod.site

- brightlogicassets.com

- safecloudassets.com

- lightwaveassets.com

- cascadepointassets.com

- getxmlppa.com

- syncxmlvyt.com

- interactive-fics.vercel.app

- blookethackerpro.vercel.app

- editanything3xmetoda.vercel.app

- hpext-9udj.vercel.app

- kahoot-ten-gamma.vercel.app

- t25695268@gmail.com

- mark23746732677@gmail.com

- tom252266@gmail.com

- john24234234222@gmail.com

- paul2372732987@gmail.com

- c9351683@gmail.com

- paperpanda2024@gmail.com

- vytalextension@gmail.com

- mrek353ser@gmail.com

- mustwsko35@gmail.com

- extpool2025@gmail.com

TTPs

| Tactic | Technique |

| Resource Development | LX2.001(T1588) – Obtain Capabilities |

| Credential Access | LX8.008 – Network Tampering |

| Discovery | LX9.003 (T1082) – System Information Discovery |

| Command and Control | LX11.004 – Establish Network Connection |

| Impact | LX13.004.1 (T1565) – Data Manipulation: Content Manipulation |

Remediation & Mitigation

For Users

-

Remove extensions that load remote configuration files – anything fetching config.php or theme.php from unknown servers is a risk.

-

Avoid extensions that modify web content without clear justification – DOM rewriting + remote content = high-risk.

-

Prefer high-reputation, well-known developers – avoid “new”, “unknown”, or low-review extensions.

-

Review extension activity using Chrome’s built-in extension tools – look for unexpected network connections.

For Security Teams

-

Detect common artifacts – Flag extensions that:

- Fetch remote injection configs

- Use timestamped cache-bypassing queries

- Define injection rules with selectors and patterns

- Use MutationObservers aggressively

- Use Chrome Debugger APIs unnecessarily

-

Perform behavioral sandbox testing – Monitor:

- DOM changes

- Outbound network calls

- Modified elements

Timing of remote configuration pulls

-

Block known malicious asset domains – Monitor for domains related to these extension families.